Architecture in Not reality

blog post - 22 Jan 2026

The relationship between architecture and reality often dwells in subtle tension—a negotiation between the tangible and the imagined. For many designer, this duality shapes their craft, reframing structures as vessels for memory, identity, and aspiration. While reality demands functional compliance with physical laws and constraints, architecture operates within a realm where form and spirit converge, creating spaces that transcend mere utility.

This essay explores how design, as a reflection of human consciousness, becomes a “sign or mark from our memory,” pushing architecture beyond the physical to articulate the intangible imprints left by people who inhabit and engage with these spaces.

In the pursuit of algorithmic architecture reveals a quiet rebellion against rigid forms, urging us to reconsider how technology reshapes not just structures, but our collective perception of living spaces. Amid algorithmic precision, the architect must also retain a reverence for the human experience, ensuring that spatial transitions—from residential sanctuaries to public realms—remain attuned to individual and communal needs.

This balance between computation and empathy defines their commitment to elevating spatial importance in living spaces, transforming sterile geometries into places that nurture connection rather than impersonal utility. At the heart of this mission lies a belief that architecture, in its quest to merge logic with emotion, must act as a mediator between abstract intent and lived reality. While striving to make algorithmic optimization with human-centric design, architects often grapple with the paradox of “not reality”—a tension where the fragmented essence of tradition competes with the immediacy of modernity.

Yet this contradiction fuels creativity: algorithms can simulate organic patterns, yet authenticity remains elusive. The result is spaces that feel both futuristic and familiar, where data-driven precision coexists with organic evolution. This interplay challenges conventional notions of progress, asserting that true spatial significance arises not solely from technological advancement but from how those innovations serve collective well-being.

Ultimately, architecture challenges us to preserve the flexibility of thought while honoring its role as a custodian of memory. In redefining “not reality,” we refine a concept that, despite its contradiction, remains central: architecture shapes how people perceive and dream within the built environment. Though straddling moments of abstraction, it affirms its enduring power to shape human existence, blurring lines between the ephemeral and the eternal.

Through this pursuit, the architect affirms their role not merely as designer, but as curator of shared human experience, ensuring that even in their “not reality” realm, spaces reflect the profound depth of the spaces they inhabit.

Architecture in Not reality

You didn’t come this far to stop

blog post - 22 Jan 2026

Architecture exists most powerfully in what it imagines, not what it builds

Architecture's deepest purpose has never been shelter alone. Across three centuries of visionary practice—from Enlightenment "paper architects" to Soviet dissenters, from German Expressionists to Japanese Metabolists, from deconstructivist philosophers to contemporary phenomenologists—a persistent counter-tradition reveals that architecture achieves its fullest meaning in the tension between physical reality and the imagined, between the measurable and unmeasurable. This is architecture "in not reality": buildings that were never built, spaces that exist only in drawings, theories that position architecture as a vessel for memory, identity, imagination, and meaning that transcends mere utility. For teams exploring architecture's role as curator of human experience, this historical and philosophical lineage provides rich precedent for understanding that what we imagine architecturally may matter as much as what we construct.

When building became impossible, architecture became free

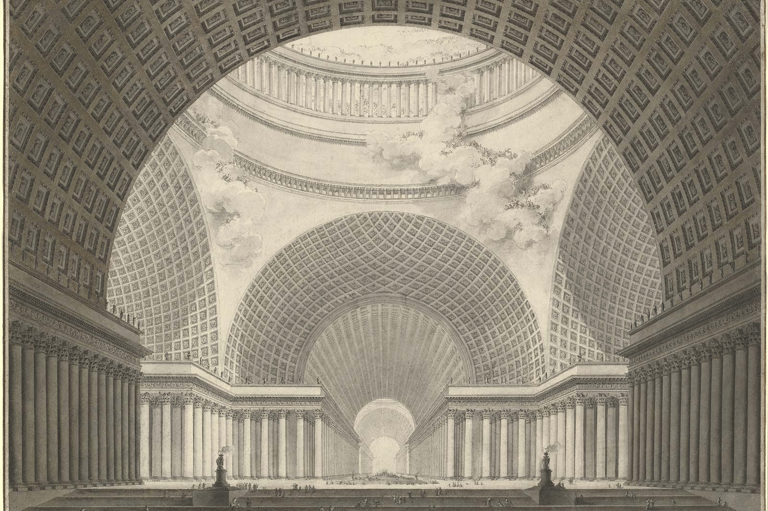

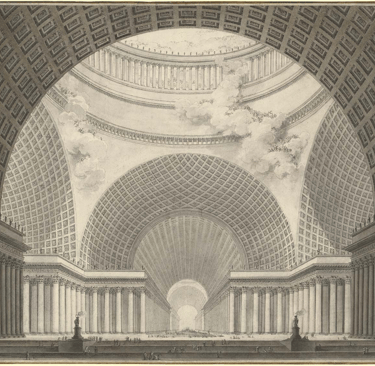

The paradox of visionary architecture is that constraint produces liberation. The French Revolutionary architects Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux worked during a period of such social upheaval that their most ambitious designs could never be realized—yet this impossibility freed them to explore architecture's ultimate potential. Boullée's Cenotaph for Isaac Newton (1784), a 150-meter hollow sphere containing only the scientist's sarcophagus and an artificial starfield pierced through its shell, was never meant to be built. It was architecture as cosmological meditation: "I have tried to create a work that no one has seen and no one can see except in imagination," Boullée wrote. His treatise fundamentally challenged 1,700 years of architectural theory by declaring that "architecture is not, as Vitruvius claimed, the art of building"—construction was merely the "scientific part," while architecture proper was an art of conceiving images.

Ledoux extended this vision into complete social reform. His Ideal City of Chaux included buildings where form literally embodied function: the House of the River Surveyor straddled a waterfall with water flowing through its center; the Coopers' Workshop was a sphere containing barrel-making operations—the building as enlarged version of its product. Yet Chaux was also a moral philosophy encoded in stone, where "the poet-architect builds a monument that will speak to the eye, the mind, and the heart." Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Carceri d'Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons) operated differently still—impossible spaces of infinite recession, stairs leading nowhere, massive stones combining Roman, medieval, and fantastic elements. The art historian Marguerite Yourcenar called them "the finest possible definition of the prison—an unlimited, inescapable place." These were not failed proposals but complete works: architecture as philosophical proposition, requiring no construction to achieve its effect.

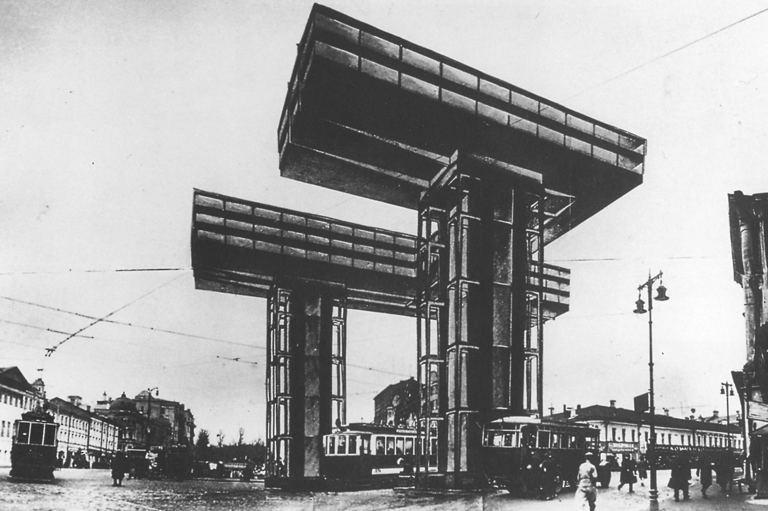

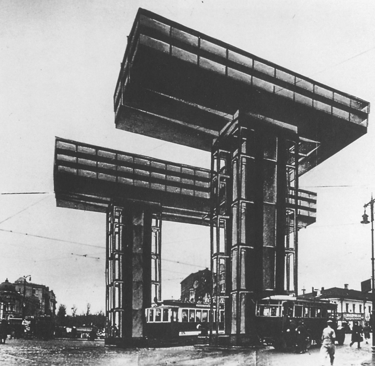

Two centuries later, Soviet "Paper Architects" discovered the same freedom through different constraints. Under Brezhnev's stagnation, Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin produced dense ink-black etchings of impossible structures because "we were the freest architects in the world—we knew nothing would be built." Their Columbarium Architecturae / Museum of Disappearing Buildings (1984) enclosed miniature models of destroyed or never-built architecture within a circular shrine—a cenotaph for architecture itself. Yuri Avvakumov's Portable Mausoleum (1986) reimagined Lenin's Mausoleum as a collapsible, traveling prop, profaning Soviet sacred space through absurdist mobility. Where the Enlightenment visionaries believed transformed societies might build their dreams, the Soviet paper architects knew—and desired—that their work would remain unrealized. Drawing became architecture's purest form.

Crystal cathedrals and floating cities dreamed of transforming consciousness

German Expressionist architecture emerged from the trauma of World War I with explicitly spiritual ambitions. Bruno Taut's Glass Pavilion (1914), built for the Cologne Werkbund Exhibition with prismatic glass in yellow, white, and blue, embodied the belief that transparent architecture could spiritually elevate humanity. Inscribed with poet Paul Scheerbart's aphorisms—"Colored glass destroys hatred"—the pavilion was designed to transform visitors through colored light experience. After the war, Taut's Alpine Architecture (1919) proposed transforming the entire Alpine mountain range into crystalline temples and luminous structures—the "Crystal House" at Monte Rosa's summit, a "Star Temple" radiating colored light. This was explicitly utopian, what Taut called "architecture of the soul rather than buildings to be constructed."

The secret Glass Chain correspondence (1919-1920) among fourteen architects using pseudonyms—Taut as "Glas," Hans Scharoun as "Hannes," Walter Gropius as "Mass"—produced hundreds of drawings of impossible structures. These deliberately non-constructible works explored architecture freed from all material and social constraints: buildings as living organisms, temples expressing cosmic forces. Erich Mendelsohn's swift, curving sketches, many created in WWI trenches, captured "function streams" rather than buildings—architecture as frozen movement that preceded and transcended buildability. His Einstein Tower (1921) expressed relativity through architectural dynamism: smooth sculptural forms avoiding any straight line, a building embodying cosmic and scientific ideas through form.

Japanese Metabolism, emerging at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo, responded not to destruction but to hyper-growth. Where Expressionism retreated into spiritual vision, Metabolism projected technological mastery. The Metabolist Manifesto declared architecture must "metabolize"—shedding outdated parts and growing new ones like living organisms. Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972), with 140 prefabricated capsules designed for replacement attached to concrete cores, represented the movement's most famous built realization. Yet most Metabolist visions remained unrealized: Kenzo Tange's Tokyo Bay Plan proposed a linear city across the bay; Kiyonori Kikutake's Marine City imagined cylindrical towers rising from artificial islands; Kurokawa's Helix City made the DNA metaphor literal. Arata Isozaki's darker City in the Air (1962) showed building clusters hovering over ruined Shinjuku—a counterpoint acknowledging that the future city might also be ruins. The distinction between what got built and what remained imagined was not failure but philosophical choice: the conceptual project preserved possibilities that construction would inevitably compromise.

Deconstructivism revealed the instabilities architecture had always concealed

The 1988 MoMA exhibition "Deconstructivist Architecture" curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley codified a movement that understood architecture as fundamentally conceptual. The seven architects featured—Peter Eisenman, Bernard Tschumi, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Frank Gehry, Coop Himmelb(l)au, and Rem Koolhaas—shared a conviction that buildings should "disturb the purity of form" rather than resolve into stable wholes. Drawing on philosopher Jacques Derrida's deconstruction, they challenged binary oppositions embedded in Western thought: inside/outside, structure/ornament, form/function, presence/absence. Architecture became a site for demonstrating that what seems solid and stable is always already unstable, that meaning is never fixed but endlessly deferred.

Bernard Tschumi's theoretical framework, articulated in Architecture and Disjunction (1994), argued that architecture should not be understood through form or function but through events—actions, movements, and bodies inhabiting space. His Parc de la Villette (1982-1998) deployed 35 red steel "folies" on a rigid grid, each deconstructing a 10-meter cube, creating a system where meaning remains perpetually fragmented. "There is no architecture without action, no architecture without events," Tschumi wrote. The violence of architecture—how buildings constrain bodies—becomes not a problem to solve but a productive tension to reveal.

Peter Eisenman's collaboration with Derrida on Choral Work for la Villette (1985-1987) explicitly tested whether architecture could embody philosophical deconstruction. Working with Plato's concept of chora—the receptacle that receives forms without being a form—Eisenman superimposed grids and traces to create palimpsest effects. That the project remained largely unbuilt became philosophically apt: it exists as a trace itself, exceeding any possible built form. Eisenman's Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Berlin, 2005) extends this logic: 2,711 concrete stelae of varying heights on undulating ground create disorientation without representation—no names, no narrative, no images. The memorial argues that conventional architecture cannot contain the Holocaust; it can only register absence bodily.

Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum Berlin (2001) uses voids—empty vertical shafts cutting through the entire building—to make absence architecturally present. These spaces remain inaccessible to visitors as exhibition space; they embody what cannot be collected, displayed, or explained. The building's zigzag form emerged from mapping addresses of Jewish Berliners onto a city plan—architecture as trace of absence. Libeskind wrote: "The building is conceived as an emblem of an invisible, irrationally connected star which shines with its absent light." Deconstructivism demonstrated that architecture's "reality" necessarily includes the imaginary, conceptual, and absent—that meaning exceeds and destabilizes physical form.

Six architect-philosophers proved the unmeasurable exceeds the measurable

Certain architects have articulated particularly profound philosophies of architecture as more than physical structure. Louis Kahn (1901-1974) distinguished between "the measurable" (physical construction) and "the unmeasurable" (spiritual essence). His famous question—"What does the building want to be?"—was not whimsy but serious ontology: architectural forms possess essential natures the architect must discover rather than impose. "I asked the brick what it liked, and the brick said, 'I like an arch,'" Kahn recounted. His Salk Institute's empty travertine court channels a water course toward the Pacific, becoming what he called "a façade to the sky"—architecture addressing cosmic rather than merely functional concerns.

Aldo Rossi (1931-1997) theorized architecture as repository of collective memory. His Architecture of the City (1966) argued that urban artifacts embody the accumulated memory and identity of civilizations. The Cemetery of San Cataldo (1971-1984) uses elemental geometric forms—cone, cube, truncated house—evoking archetypal images of death and dwelling. His floating Teatro del Mondo (1979-1980) for the Venice Biennale was architecture as theater, literally suspended between reality and imagination, drawing together memories of Venetian tradition without permanent foundation.

Peter Zumthor (b. 1943) represents phenomenological architecture's focus on atmosphere and sensory experience. His Atmospheres (2006) identifies the immediate emotional response upon entering a space—"What on earth is it that moves me?"—as architecture's essential gift. The Therme Vals (1996), carved into a Swiss mountainside using locally quarried gneiss, creates full-body sensory experience: moving through dark and light spaces, warm and cool water, echoing chambers. The Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (2007) was cast around a tent of tree trunks subsequently burned away, leaving a charred cavity open to the sky—architecture materializing the tension between earth and heaven.

Tadao Ando (b. 1941) seeks spiritual awakening through minimalist concrete forms. His Church of the Light (1989) is a simple concrete box with a cruciform slot through which light forms a glowing cross—minimal means achieving maximum spiritual effect. "Light is the origin of all being," Ando writes. John Hejduk (1929-2000) developed architecture as storytelling through his "Masques"—traveling architectural characters with names, histories, and symbolic meanings: the Sleeper, the Vagabond, the Victim, the Executioner. His Berlin Masque (1981-1983) proposed 67 structures as allegory about memory, loss, and the city's traumatic history. For Hejduk, buildings are vessels of meaning, "characters in stories about human experience."

Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012) pursued architecture almost entirely through drawing, consciously refusing to build because "building always means compromise—giving up the potential of an idea." His War and Architecture project (1993) proposed parasitic structures built into war-damaged Sarajevo buildings—not restoration but transformation, scars turned into new spaces. Architecture as resistance, healing, and radical possibility: "Without experimentation, without a willingness to ask hard questions and accept disturbing answers, architecture becomes mere building."

Theory reveals architecture dwelling between tangible and intangible

Architectural phenomenology, emerging in the late 20th century, redirected attention from architecture as object to architecture as lived experience. Juhani Pallasmaa's The Eyes of the Skin (1996) critiques the "hegemony of the eye" that reduces buildings to visual spectacles. Architecture should engage all senses—touch, texture, temperature, acoustic properties, smell. "I confront the city with my body," Pallasmaa writes; "my legs measure the length of the arcade." Christian Norberg-Schulz's Genius Loci (1979) systematized the ancient Roman concept of place-spirit: each location possesses distinctive character requiring architectural acknowledgment. Architecture's fundamental task is to make this genius loci manifest—transforming abstract space into meaningful place.

Gaston Bachelard's The Poetics of Space (1958) explores how humans inhabit space imaginatively. The house is the "first universe," a microcosm organizing experience of the larger world: the cellar as dark unconscious realm, the attic as luminous intellectual retreat, corners as spaces of condensed being. Architecture's power lies not just in evoking memories but in stimulating poetic imagination—the capacity to transform and transcend. His concept of "topophilia" (love of place) suggests humans have fundamental need for spaces that shelter imagination and memory.

Semiotic approaches treat architecture as a system of signs communicating meaning beyond function. Robert Venturi's Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) rejected modernist reductivism—"less is a bore"—advocating that architecture embrace multiple elements, meanings, and references. Charles Jencks identified "double-coding" in postmodern architecture: buildings simultaneously addressing architects and the public through layered meanings. All these frameworks share a fundamental critique: pure functionalism ignores the psychological, spiritual, and cultural dimensions of dwelling. The "intangible" dimensions are not luxuries but necessities for authentic human habitation.

The tradition points toward architecture as thought made inhabitable

What emerges from this historical survey is a persistent counter-tradition understanding that architecture exists simultaneously in multiple registers. The physical building is real—it has weight, material, structure, cost—but so too is the experiential reality of atmosphere and feeling, the cultural reality of memory and meaning, and the imaginative reality of possibility and aspiration. The most profound architecture exists precisely in the tension between these registers: between what is built and what is imagined, between the measurable and unmeasurable, between presence and absence.

Several key insights emerge for any team exploring architecture's role as curator of human experience:

The unbuilt project constitutes legitimate architecture. From Boullée's cosmic spheres to Woods's war architecture, the drawing or model can be the complete work—not a failed building but a pure architectural proposition freed from the compromises of construction.

Impossibility liberates imagination. Constraint—whether revolutionary chaos, Soviet bureaucracy, or wartime trauma—has repeatedly produced architecture's most visionary moments. When "real" building becomes impossible, architecture discovers its capacity to address what transcends utility.

Architecture mediates between realms. Every significant theoretical framework positions architecture as bridging oppositions: physical/spiritual (Kahn), past/present (Rossi), material/experiential (Zumthor), presence/absence (deconstructivism), body/consciousness (phenomenology).

Memory and meaning are architectural materials. Collective memory (Rossi), poetic imagination (Bachelard), genius loci (Norberg-Schulz), and trace (Derrida) are not decorations applied to functional structures but constitutive elements of what architecture is.

The critique of functionalism is universal. From Boullée's rejection of "servile practice" to phenomenology's attack on ocularcentrism, this tradition insists that architecture addressing only program has abandoned its essential purpose.

Conclusion: Architecture's fullest reality includes what it imagines

The lineage traced here—visionary architects, Expressionists, Metabolists, deconstructivists, architect-philosophers, phenomenologists—represents not a marginal curiosity but a central strand of architectural thought. It suggests that architecture achieves its highest calling not when it solves practical problems but when it addresses fundamental questions of human existence: How do we dwell? What do we remember? What might be otherwise?

For teams exploring these territories, this history provides both precedent and permission. Architecture has always existed "in not reality"—in the space between the tangible and intangible, between the built fact and the imagined possibility. The discipline's most significant practitioners understood that what we imagine architecturally shapes reality as powerfully as what we construct. Boullée's cosmic spheres, Taut's crystal temples, Tschumi's folies, Libeskind's voids, and Woods's parasitic structures all insist that architecture's role as curator of human experience, memory, and meaning extends far beyond functional compliance—into the essential territory where imagination and reality perpetually negotiate their boundaries.